Stress and Trauma Within the COVID-19 Pandemic

Co-authored by Joanna Lilley, Leah Madamba, and Steve Sawyer LCSW CSAC

In a whirlwind our lives have changed, everything we have known from our regular morning rituals, access to groceries, and even our freedom to travel. The “adulting” world has been dramatically uprooted and this has kept most of us adults hyper-focused on adapting our adult lives. Many people are slowly adjusting to the “new norm” in their homes and professional lives. Now . . . what about the kiddos?

From Hallways of Interaction and Isolation Through Screens

Social life is at the center of every teenager, and they are that way by design. Pair this need for social interaction with the “Individuation” stage that psychologist Erick Erickson theorized and you have a royal combination of challenges in the current Quaran-teen predicament. With being isolated from all in-person interaction, aloneness becomes a real issue when it comes to these current safety measures.

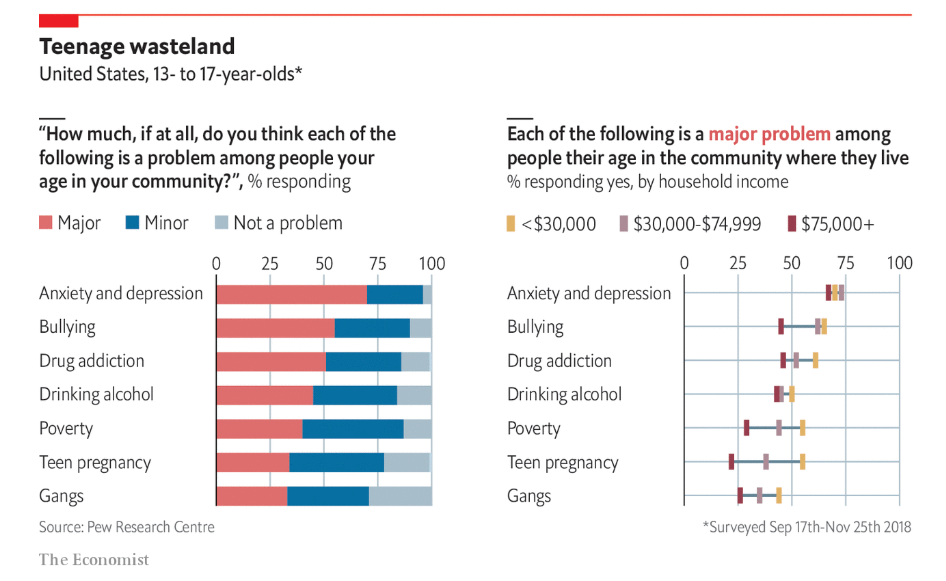

There were already warning signs in our Pre-epidemic youth with current trends of dysfunction in the overuse of phones, texting, video games and social media. The most alarming warning sign is that Suicide and Anxiety rates were already at an all time high and on the upward trajectory. See figure below:

Another image demonstrating our adolescents struggling can be seen in this image:

We are now faced with having to allow these deeply embedded social needs met only via the virtual world, potentially pushing our youth into further isolation during challenging times. The ability to enforce electronic limits is essential for mental health but take it too far and we then risk refusal to follow social distancing protocols. We are in a tough parenting situation, and even forced to bend our parental morals.

With Isolation on the increase, out of necessity we begin to risk damage that will be difficult to reverse. Aloneness is often the largest and most painful part of any traumatic event.

Differentiating Trauma and Acute Stress Response

When we look at stressful situations we often use the word Trauma. There is no denying that this is an extremely stressful time. There are four key factors when we look at high stress scenarios to be considered: High level of distress, Powerlessness real or perceived, Aloneness/Isolation, and Lasting residual symptoms post event. In the criteria of Post Traumatic Stress as a mental health illness, symptoms must still be present 1 month post event or threatening situation. Many of the largest anticipated acute stress symptoms become difficult to differentiate from PTSD when they are generalized or do not have specific triggers.

Based on these four factors, it is apparent that our society is in a time of high stress, and the outcome of this for each individual will be largely based on their perception and the coping mechanisms they choose. For those that perceive that they are powerless and sink back into a time of isolation, they could experience a larger stress response. Contrast this with the response of people who are using this time to reconnect to important people in their lives and choosing to see this time as an opportunity to shift their decisions. They will likely come out of this time with a renewed sense of purpose. That is how many people can live through the same event yet have vastly different experiences and takeaways from it.

Trauma: The Long Game After Effect, Pathology vs Adaptation

As mental health professionals throughout this pandemic the word Trauma has often been thrown around as a label to summarize the emotional and reactive experiences of the Pandemic. When examining the most common mental health diagnosis for Trauma we look to the criteria for the diagnosis of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) listed in the mental health diagnosis manual the Diagnostic Static Manual the DSM-TR.

The criteria for PTSD as give by the DSM TR Diagnosis Manual are:

Criterion A: stressor (one required)

The person was exposed to: death, threatened death, actual or threatened serious injury, or actual or threatened sexual violence, in the following way(s):

Direct exposure

Witnessing the trauma

Learning that a relative or close friend was exposed to a trauma

Indirect exposure to aversive details of the trauma, usually in the course of professional duties (e.g., first responders, medics)

Criterion B: intrusion symptoms (one required)

The traumatic event is persistently re-experienced in the following way(s):

Unwanted upsetting memories

Nightmares

Flashbacks

Emotional distress after exposure to traumatic reminders

Physical reactivity after exposure to traumatic reminders

Criterion C: avoidance (one required) Avoidance of trauma-related stimuli after the trauma, in the following way(s):

Trauma-related thoughts or feelings

Trauma-related external reminders

Criterion D: negative alterations in cognitions and mood (two required)

Negative thoughts or feelings that began or worsened after the trauma, in the following way(s):

Inability to recall key features of the trauma

Overly negative thoughts and assumptions about oneself or the world

Exaggerated blame of self or others for causing the trauma

Negative affect

Decreased interest in activities

Feeling isolated

Difficulty experiencing positive affect

Criterion E: alterations in arousal and reactivity

Trauma-related arousal and reactivity that began or worsened after the trauma, in the following way(s):

Irritability or aggression

Risky or destructive behavior

Hypervigilance

Heightened startle reaction

Difficulty concentrating

Difficulty sleeping

Criterion F: duration (required)

Symptoms last for more than 1 month.

Criterion G: functional significance (required)

Symptoms create distress or functional impairment (e.g., social, occupational).

Criterion H: exclusion (required)

Symptoms are not due to medication, substance use, or other illness.

A key factor to highlight within the diagnosis of PTSD is that the symptoms must last for more than one month following an event or contact to the threat. Using the standard trauma definition proves challenging in this pandemic situation because the threat will likely be an ongoing issue. Pandemic issues will not clearly fit the criteria of PTSD until the threat is both gone and symptoms persist throughout time. This will be a key factor in demonstrating functional impairment is lasting through the test of time.

The test of time is a key factor for determining whether stress responses are an action necessary to preserve both our own safety and our lasting survival. In this case we need to be diligent about not pathologizing terms like “traumatized” and have a more healthy view of our current behavioral manifestations as “adapting” behavior. Adapting behavior is seen as healthy, Trauma has a connotation of pathology.

Examining our Childhood Stress Lessons from Developmental Trauma Research

With the current pandemic situation it is important to recognize the differences of stress response based upon age. Children often respond differently from adults and modern research of children in traumatic situations long term offer some indicators for what to look for.

The outcomes that differentiate stress responses experienced early in life with events like those in the now widely accepted ACES research show an outcome in early youth exposure to Toxic stress. Two key studies that have paved the way to the proposed diagnosis of Developmental Trauma Disorder have mapped childrens common symptoms when immersed in toxic stress over time. Unseen Wounds: A Childhood Study of Maltreatment and Where No Where is Safe both extensively investigated childhood specific stress response when immersed in threat over time. These studies paved the way to separate the symptoms of children of trauma stress responses from that of the adult focused diagnosis of PTSD stress responses.

The some of the key criteria are outlined in this chart below.

As we can see in this chart the key differentiator is a wide spanning dysregulation. Dysregulation is often defined as; Abnormality or impairment in the regulation of a metabolic, physiological, or psychological process. In the Unseen Wounds study this dysregulation was found to often be witnessed in children through hyperactivity, rapidly fluctuating moods and emotions, and an inability to focus.

The ramifications of dysregulation is a well researched and supported stress response in children is also now compounded with social isolation and home schooling dynamics. The combination of inability to “play” out dysregulatory energy with other children and the drive towards electronic based education in some ways may build the pressure of a stress “time bomb” if not directly targeted and released from a developing nervous system. It is highly likely that this will show itself with lasting effects in our children, however time will be the only true factor in identifying the current pandemic as traumatizing to our children. The symptoms above need to be carefully researched in the years ahead and parents need to be educated about this being a variable in interacting with their stressed children patiently.

Grief and Loss of the Comfortable

Let’s talk about the grief and loss of “our existence as we know it” for adolescents and young adults right now. With the sudden change to so many of our normal activities, it is important to identify what we are feeling as grief and loss. As David Kessler mentions in his recent podcast with Brene Brown, our own loss is our greatest loss. So for our teens who are now not in school, this could be the biggest loss they have experienced so far in their lives. For our emerging young adults, the loss of the typical rites of passage at this age including graduation ceremonies from high school or college. This loss is being felt by thousands of young people right now.

As our current situation continues to evolve, it can feel like we are experiencing ever widening rings of grief. Initially we might have been sad about having to Stay Home and Stay Safe for two weeks. When we reached that milestone, we learned that the time frame had been extended, for some of us indefinitely. The slow unfolding of this crisis means that many of our children will continue to deal with new layers of this grief and loss, all while we as adults and parents are dealing with our own layers.

Grieving our new changes is the result of missing something before the change. This can leave us irritable, and often in a state of dis-ease. As we continue to navigate this, it can be helpful to remember the five stages of grief that David Kessler and Elisabeth Kubler-Ross identified: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. These five stages do not prescribe a linear path that we walk along but instead outline the different phases we will go through in our own unique order. Knowing this and being able to identify it as such can help us get through this while also offering support and guidance for the young people in our lives.

No More Friends, no more school and an uncertain future

As the school year wraps up many parents are now facing the reality that their summer plans are looking very different and a lot of uncertainty still exists about the fall. With school being cancelled and having our college students back at home, how does this translate to a traumatic experience? These scenarios will affect people differently. For many of our youth, they will face this time with a certain resilience that they have learned along the way. For others, this time will cause them to pull further into their shells and alienation from the outside world.

How can we support these young people right now?

Take care of yourself so you can be present for them. This might be going for a walk once a day or making sure you are staying hydrated. During these difficult times, the little aspects of self-care matter.

Continue to educate yourself about signs and symptoms of grief and loss, stress, and trauma. Being self-aware, and being aware for the sake of helping others. We are all impacted differently, and at different times. It’s important to know the signs and know how to help.

Create plans A through Z. These plans create predictability, safety and security for young people. Create plans for the summer. Then have several plans for what could play out for the fall. Be prepared to adapt. Be prepared to be flexible, and adjust accordingly.

Be Present. Take a few moments each day to be present and available for your young person to really tune in to how they are feeling and experiencing things. While these moments can be hard to find when we have so much on our plates, it is a crucial piece to understanding the difference between them feeling sad or something more serious.

Connect With Others. It is easy to isolate during these hectic times, so encourage your young person to reach out and connect with others. This can be friends, family, or even finding new friends through joining on-line class or book club.

Be Sure to PLAY. Play and the enjoyment of play are key variables in releasing held stress from our nervous systems.

Seek out Therapy. Find a TeleHealth provider that can work with anyone experiencing grief and loss, struggling with adjustments, and trauma. Also consider that one professional may not be enough. Look into additional supports to add to your team. This could include family therapy, Psychiatry, Coaching for adolescents, young adults, or parents, as well as any other professionals that feel appropriate during this time.

For questions and comments, contact:

Leah Madamba via email.

Steve Sawyer, LCSW via email.